Chapter 1: Introduction

With Professor Judea Pearl receiving the prestigious 2011 A.M. Turing Award, Bayesian networks have presumably received more public recognition than ever before. Judea Pearl’s achievement of establishing Bayesian networks as a new paradigm is fittingly summarized by Stuart Russell (2011) :

“[Judea Pearl] is credited with the invention of Bayesian networks, a mathematical formalism for defining complex probability models, as well as the principal algorithms used for inference in these models. This work not only revolutionized the field of artificial intelligence but also became an important tool for many other branches of engineering and the natural sciences. He later created a mathematical framework for causal inference that has had significant impact in the social sciences.”

All Roads Lead to Bayesian Networks

There are numerous ways we could provide motivation for using Bayesian networks. A selection of quotes illustrates that we could approach Bayesian networks from many different perspectives, such as machine learning, probability theory, or knowledge management.

- “Bayesian networks are as important to AI and machine learning as Boolean circuits are to computer science.” (Stuart Russell in Darwiche, 2009)

- “Bayesian networks are to probability calculus what spreadsheets are for arithmetic.” (Conrady and Jouffe, 2015)

- “Currently, Bayesian Networks have become one of the most complete, self-sustained and coherent formalisms used for knowledge acquisition, representation and application through computer systems.” (Bouhamed et al., 2015 )

In this first chapter, however, we approach Bayesian networks from the perspective of analytical modeling. Given the current prominence of analytics, our aim is to position Bayesian networks in relation to traditional statistical methods and, in addition, to compare them with more recent developments in data mining. This context is especially relevant in light of the attention that Big Data and related technologies now receive. Their dominance in public discourse may overshadow other valuable methods of scientific inquiry, methods whose relevance becomes clear through the application of Bayesian networks.

Once we have established how Bayesian networks fit into the broader “world of analytics,” Chapter 2 introduces the mathematical formalism that underpins the Bayesian network paradigm. This chapter draws heavily on a technical report by Judea Pearl, providing an authoritative foundation. While BayesiaLab has made it remarkably easy to apply Bayesian networks in research, it is essential to underscore the role of theory. A solid grasp of the underlying principles is key to using Bayesian networks correctly and effectively.

Chapter 3 concludes the first part of the book with an overview of the BayesiaLab software platform. Here, we illustrate how the theoretical strengths of Bayesian networks are operationalized in a versatile research tool, applicable across a wide range of domains, from bioinformatics to marketing science and beyond.

A Map of Analytic Modeling

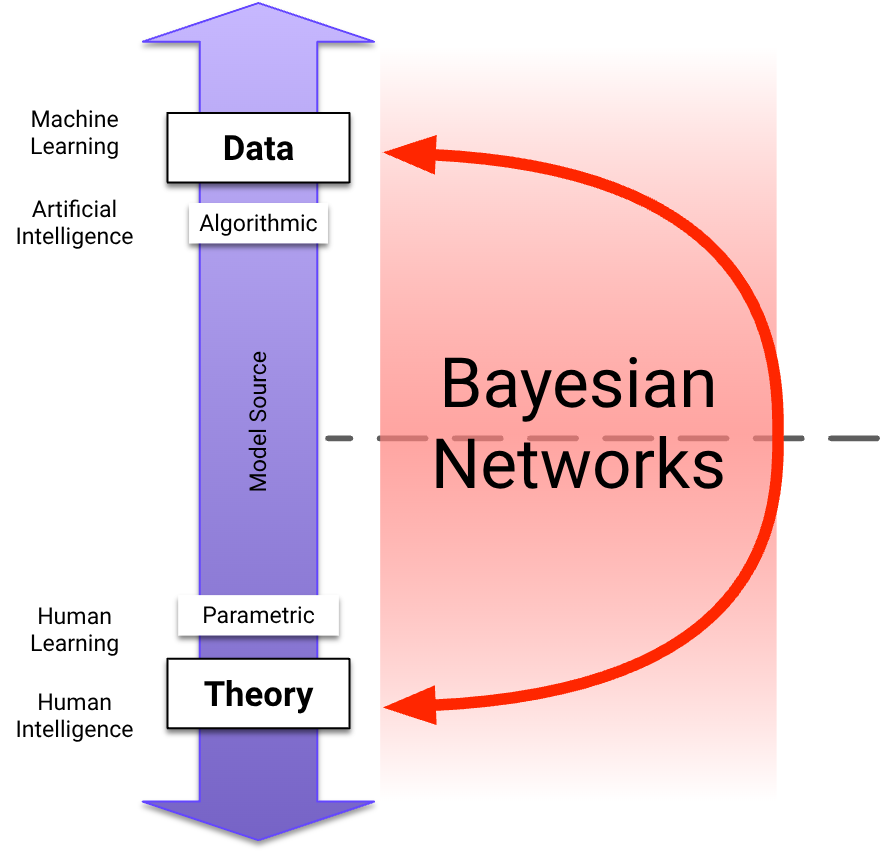

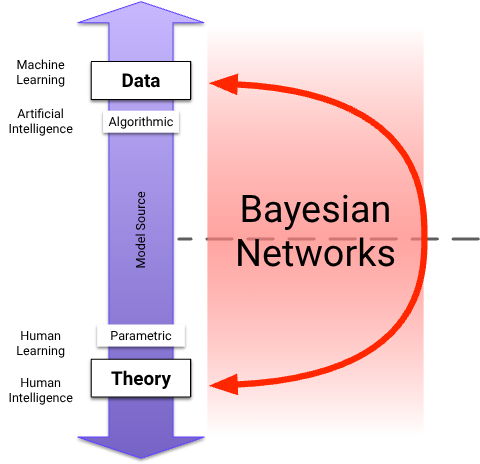

Following the ideas of Breiman (2001) and Shmueli (2010) , we create a “map of analytic modeling” that is defined by two axes:

- The x-axis reflects the Modeling Purpose, ranging from Association/Correlation to Causation. Labels on the x-axis indicate a conceptual progression, including Description, Prediction, Explanation, Simulation, and Optimization.

- The y-axis represents the Model Source, i.e., the source of the model specification. Model Source ranges from Theory (bottom) to Data (top). Theory is also tagged with Parametric as the predominant modeling approach. Additionally, it is tagged with Human Intelligence, hinting at the origin of Theory. On the opposite end of the y-axis, Data is associated with Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence. It is also tagged with Algorithmic in contrast to Parametric modeling.

Needless to say, this map displays a highly simplified view of the world of analytics. Despite this caveat, we will use this map and its coordinate system to position different modeling approaches.

Quadrant 2: Predictive Modeling

Many of today’s predictive modeling techniques are algorithmic and would fall mostly into Quadrant 2. In Quadrant 2, a researcher would be primarily interested in the predictive performance of a model, i.e., is of interest.

Neural networks are a typical example of implementing machine learning techniques in this context. Such models often lack theory. However, they can be excellent “statistical devices” for producing predictions.

Quadrant 4: Explanatory Modeling

In Quadrant 4, the researcher is interested in identifying a model structure that best reflects the underlying “true” data-generating process, i.e., we are looking for an explanatory model. Thus, the function is of greater interest than :

Traditional statistical techniques that have an explanatory purpose and are used in epidemiology and the social sciences would mostly belong in Quadrant 4. Regressions are the best-known models in this context. Extending further into the causal direction, we would progress into the field of operations research, including simulation and optimization.

Despite the diverging objectives of predictive modeling versus explanatory modeling, i.e., predicting versus understanding , the respective methods are not necessarily incompatible. In our map, this is suggested by the blue boxes that gradually fade out as they cross the boundaries and extend beyond their “home” quadrant. However, the best-performing modeling approaches do rarely serve predictive and explanatory purposes equally well. In many situations, the optimal fit-for-purpose models remain very distinct from each other. In fact, Shmueli (2010) has shown that a structurally “less true” model can yield better predictive performance than the “true” explanatory model.

We should also point out that recent advances in machine learning and data mining have mostly occurred in Quadrant 2 and disproportionately benefited predictive modeling. Unfortunately, most machine-learned models are remarkably difficult to interpret in terms of their structural meaning, so new theories are rarely generated this way. For instance, the well-known Netflix Prize competition produced well-performing predictive models but yielded little explanatory insight into the structural drivers of choice behavior.

Conversely, in Quadrant 4, developing explanatory models through machine learning remains challenging. Unlike in Quadrant 2, having an ever-increasing amount of data does not necessarily aid in discovering theory via machine learning.

Bayesian Networks: Theory and Data

Concerning the horizontal division between Theory and Data on the Model Source axis, Bayesian networks have a special characteristic. Bayesian networks can be built from human knowledge, i.e., from Theory, or they can be machine-learned from Data. Thus, they can use the entire spectrum as a Model Source.

Due to their graphical structure, machine-learned Bayesian networks are visually interpretable, which promotes human learning and theory building. As shown by the bidirectional arc in the following diagram, Bayesian networks enable human and machine learning to work together. In other words, Bayesian networks can be developed through a combination of human and artificial intelligence.

Bayesian Networks: Association and Causation

Beyond crossing the boundaries between Theory and Data, Bayesian networks also have special qualities concerning causality. Under certain conditions and with specific theory-driven assumptions, Bayesian networks facilitate causal inference. In fact, Bayesian network models can cover the entire range from Association/Correlation to Causation, spanning the entire x-axis of the map below. In practice, this means that we can add causal assumptions to an existing non-causal network and, thus, create a causal Bayesian network. This is particularly important when we try to simulate an intervention in a domain, such as estimating the effects of a treatment. Working with a causal model is imperative in this context, and Bayesian networks help us make that transition.

As a result, Bayesian networks are a versatile modeling framework suitable for many problem domains. The mathematical formalism underpinning the Bayesian network paradigm will be presented in the next chapter.