Key Driver Analysis

Our Probabilistic Structural Equation Model is now complete, and we can use it to perform the analysis part of this exercise, namely to find out what “drives” Purchase Intent. We return to the Validation Mode

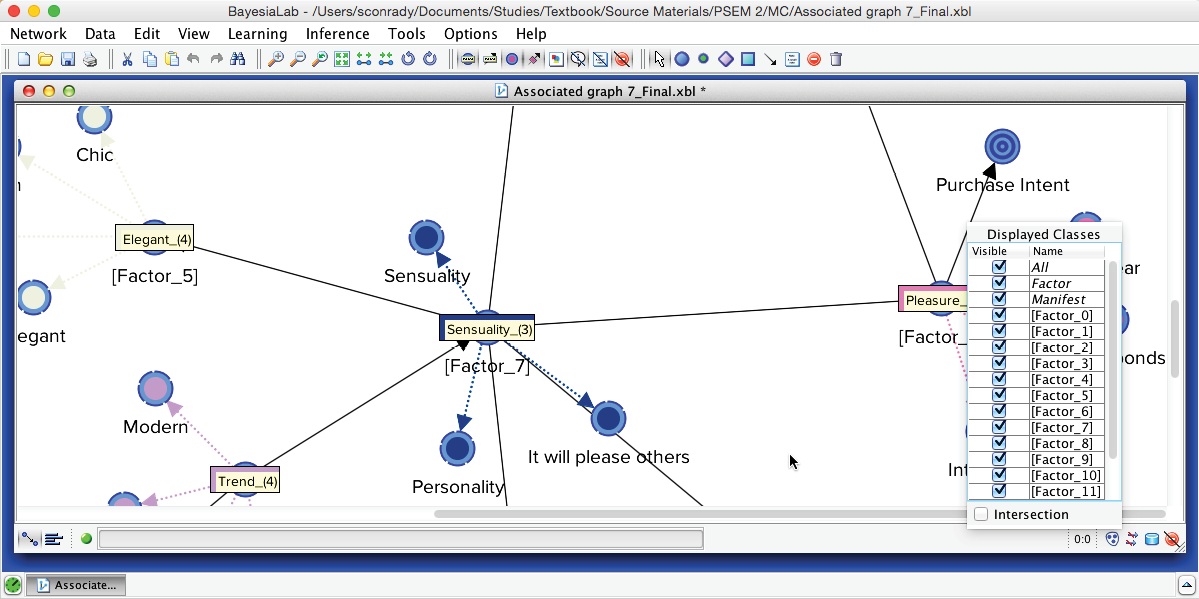

To understand the relationship between the factors and Purchase Intent, we want to “tune out” all Manifest variables for now. We can do so by right-clicking the Classes icon in the bottom right corner of the Graph Panel window. This brings up a list of all Classes. By default, all are checked and thus visible.

For our purposes, we want to un-check All and then only check the class Factor.

.png)

In the resulting view, all the Manifest Nodes are transparent, so the relationship between the Factors becomes visually more prominent. By de-selecting the Manifest Nodes in this way, we also exclude them from the following visual analysis.

Target Analysis

In line with our objective of learning about the key drivers in this domain, we proceed to analyze the association of the newly created Factors with Purchase Intent.

We return to the Validation Mode , in which we can use two approaches to learn about the relationships between Factors and the Target Node: we first perform a visual analysis and then generate a report in table format.

Visual Analysis

We initiate the visual analysis by selecting Menu > Analysis > Visual > Target Mean Analysis > Standard:

.png)

This brings up a dialog box with the options shown below. Given the context, selecting Mean for both the Target Node and the Nodes is appropriate.

.png)

Upon clicking Display Sensitivity Chart, the resulting plot shows the response curves of the Target Node as a function of the values of the Factors. This allows an immediate interpretation of the strength of the associations.

.png)

Target Analysis Report

As an alternative to the visual analysis, we now run the Target Analysis Report: Menu > Analysis > Report > Target Analysis > Total Effects on Target.

.png)

Although “effect” carries a causal connotation, we must emphasize that we strictly examine associations. This means that we perform observational inference as we generate this report.

A new window opens up to present the report. Under Menu > Options > Settings > Reporting, we can check Display the Node Comments in Tables so that Node Comments appear in addition to the Node Names in all reports.

.png)

The Total Effect (TE) is estimated as the derivative of the Target Node with respect to the driver node under study.

where is the analyzed variable and is the Target Node. The Total Effect represents the change in the mean of the Target Node associated with—and not necessarily caused by— a small modification of the mean of a driver node. The Total Effect is the ratio of these two values.

This way of measuring the effect of the Factors on the Target Node assumes the relationships to be locally linear. Even though this is not always a correct assumption, it can be reasonable to simulate small changes in satisfaction levels.

As per the report, [Factor_2] provides the strongest Total Effect with a value of 0.399. This means that observing an increase of one unit in the level of the concept represented by [Factor_2] predicts a posterior probability distribution of Purchase Intent that has an expected value that is 0.399 higher compared to the marginal value.

The Standardized Total Effect (STE) is also displayed. It represents the Total Effect multiplied by the ratio of the standard deviation of the driver node and the standard deviation of the Target Node.

This means that Standardized Total Effect takes into account the “potential” of the driver under study.

In the report, the results are sorted by the Standardized Total Effect in descending order. This immediately highlights the order of importance of the Factors relative to the Target Node, Purchase Intent.

Independence Tests

In the columns further to the right in the report, the results of independence tests between the nodes are reported:

- Chi-Square () test or G-test: The independence test is computed on the basis of the network between each driver node and the target variable. It is possible to change the type of independence from the Chi-Square () test to the G-test via

Menu > Options > Settings > Statistical Tools. - Degree of Freedom: Indicates the degree of freedom between each driver node and the Target Node in the network.

- p-value: the p-value is the probability of observing a value as extreme as the test statistic by chance.

If a dataset is associated with the network, as is the case here, the independence test, the degrees of freedom, and the p-value are also computed directly from the underlying data.

Factors versus Manifest Nodes

For overall interpretation purposes, looking at Factor-level drivers can be illuminating. Often, it provides a useful big-picture view of the domain. However, we need to consider the Manifest-level drivers to identify specific product actions. As pointed out earlier, the Factor-level drivers only exist as theoretical constructs, which cannot be directly observed in data. As a result, changing the Factor nodes requires manipulating the underlying Manifest nodes. For this reason, we now switch back our view of the network in order to only consider the Manifest nodes in the analysis. We do that by right-clicking the Classes icon in the bottom right corner of the Graph Panel window. This brings up the list of all Classes, of which we only check the Class Manifest. Now, all Factors are translucent and excluded from the analysis.

.png)

We repeat both the Target Mean Analysis and the Total Effects on Target report.

.png)

Not surprisingly, the Manifest Nodes show a similar pattern of association as the Factors. However, there is one important exception: the Manifest Node Intensity shows a nonlinear relationship with Purchase Intent. The curve for Intensity is shown with a gray line. Note that by hovering over a curve or a node name, BayesiaLab highlights the corresponding item in the legend or the plot.

Also, we can see that Intensity was recorded on a 1−5 scale rather than the 1−10 scale that applies to the other nodes. Intensity is a so-called “JAR” variable, i.e., a variable that has a “just-about-right” value. In the context of perfumes, this characteristic is obvious. A fragrance that is either too strong or too light is undesirable. Instead, there is a value somewhere in between that would make a fragrance most attractive. The JAR characteristic is prototypical for variables representing sensory dimensions, e.g., saltiness or sweetness.

This emphasizes the importance of visual analysis, as the nonlinearity goes unnoticed in the Total Effects on Target report. In fact, it drops almost to the bottom of the list in the report.

It turns out to be rather difficult to optimize a JAR-type variable at a population level. For example, increasing Intensity would reduce the number of consumers who find the fragrance too subtle. On the other hand, an increase in Intensity would presumably dismay some consumers who believed the original Intensity level to be appropriate.

.png)

Constraints via Costs

As this drivers’ analysis model is intended for product optimization, we need to consider any possible real-world constraints that may limit our ability to optimize any of the drivers in this domain. For instance, a perfumer may know how to change the intensity of a perfume but may not know how to directly affect the perception of “pleasure.” In the original study, a number of such constraints were given.

In BayesiaLab, we can conveniently encode constraints via Costs, which is a Node Property. More specifically, we can declare any node as Not Observable, which — in this context — means that they cannot be considered with regard to optimization. Costs can be set by right-clicking on an individual node and then selecting Properties > Cost.

.png)

This brings up the Cost Editor for an individual node. By default, all nodes have a cost of 1.

.png)

Unchecking the box Cost or setting a value ≤0 results in the node becoming Not Observable.

.png)

Alternatively, we can bring up the Cost Editor for all nodes by right-clicking on the Graph Panel and then selecting Edit Costs from the Context Menu.

.png)

The Cost Editor presents the default values for all nodes.

.png)

Again, setting values to zero will make nodes Not Observable. Instead of applying this setting node by node, we can import a Cost Dictionary that defines the values for each node. An excerpt from the text file is shown below. The syntax is straightforward: Not Observable is represented by 0.

.png)

From within the Cost Editor, we can use the Import button to associate a Cost Dictionary. Alternatively, we can select Menu > Data > Associate Dictionary > Node > Costs.

.png)

Upon import, the Node Editor reflects the new values, and the presence of non-default values for costs is indicated by the Cost icon in the lower right-hand corner of the Graph Panel.

.png)

Furthermore, upon defining Costs, we can see that all Not Observable nodes are marked with a light purple background.

.png)

It is important to note that all Factors are also set to Not Observable in our example. In fact, we do have two options here:

- The optimization can be done at the first level of the hierarchical model, i.e., using the Manifest variables;

- The optimization can be performed at the second level of the model, i.e., using the Factors.

Most importantly, these two approaches cannot be combined as setting evidence on Factors will block information coming from Manifest variables. Formally declaring the Factors as Not Observable tells BayesiaLab to proceed with option #1. Indeed, we plan to perform optimization using the Manifest variables only.

Multi-Quadrant Analysis

The network we have analyzed thus far modeled Purchase Intent as a function of perceived perfume characteristics. It is important to point out that this model represents the entire domain of all 11 tested perfumes. However, it is reasonable to speculate that different perfumes have different drivers of Purchase Intent. Furthermore, for purposes of product optimization, we certainly need to look at the dynamics of each product individually.

BayesiaLab assists us in this task by means of Multi-Quadrant Analysis. This function can generate new networks as a function of a Breakout Node in an existing network. This is where the node Product comes into play, which has been excluded all this time. Our objective is to generate a set of networks that model the drivers of Purchase Intent for each perfume individually, as identified by the Product breakout variable.

We start the Multi-Quadrant Analysis by selecting Menu > Tools > Multi-Quadrant Analysis.

.png)

This brings up the dialog box, in which we need to set a number of options:

.png)

Firstly, the Breakout Variable must be set to Product to indicate that we want to generate a network for each state of Product. For Analysis, we have several options: We choose Total Effects to be consistent with the earlier analysis. Regarding the Learning Algorithm, we select Parameter Estimation. This choice becomes evident once the dataset representing the “overall market” is split into 11 product-specific subsets. Now, the number of available observations per product drops to only 120. Given that most of our variables have 5 states, learning a structure with a dataset that small would be challenging.

This also explains why we used the entire dataset to learn the PSEM structure, which all the products will share. However, using Parameter Estimation will ensure that the parameters, i.e., the probability tables of each network, will be estimated based on the subsets of records associated with each state of Product.

Among the Options, we check Regenerate Values. This recomputes, for each new network, the values associated with each state of the discretized nodes based on the respective subset of data.

There is no need to check Rediscretize Continuous Nodes because all discretized nodes share the same variation domain, and we required equal distance binning during the data import. However, we do recommend using this option if the variation domains are different between subsets in a study, e.g., sales volume in California versus Vermont. Without using the Rediscretize Continuous Nodes option, it could happen that all data points for sales in Vermont end up in the first bin, effectively transforming the variable into a constant.

Furthermore, we do not check the option for Linearize Nodes’ Values either. This function reorders a node’s states so that its states’ values have a monotonically positive relationship with the values of the Target Node. Applying this transformation to the node Intensity would artificially increase its impact. It would incorrectly imply that it is possible to change a perfume in a way that simultaneously satisfies consumers who rated it too subtle and those who rated it too strong. Needless to say, this is impossible.

Finally, computing all Contributions will be helpful for interpreting each product-specific network.

Upon clicking OK, 11 networks are created and saved to the Output Directory defined in the dialog box. Each network is then analyzed with the specified Analysis method to produce the Multi-Quadrant Plot.

.png)

The x-value of each point indicates the mean value of the corresponding Manifest Node, as rated by those respondents who have evaluated Product 1; the position on the y-axis reflects the computed Total Effect.

From the contextual menu, we can choose Display Horizontal Scales and Display Vertical Scales, which provide the range of positions of the other products.

.png)

Using Horizontal Scales provides a quick overview of how the product under study is rated vis-à-vis other products. The Vertical Scales compare the importance of each dimension with respect to Purchase Intent. Finally, we can select the individual product to be displayed in the Multi-Quadrant Analysis window via the Contextual Menu.

.png)

Drawing a rectangle with the cursor zooms in on the specified area of the plot.

.png)

The meaning of the Horizontal Scales and Vertical Scales becomes apparent when hovering over any dot, as this brings up the position of the other (competitive) products with regard to the currently highlighted attribute.

.png)

This means, for instance, that Product 2 and Product 7 are rated lowest and highest, respectively, on the x-scale with regard to the variable Fresh. Regarding the Total Effect on Purchase Intent, Product 12 and Product 2 mark the bottom and top end, respectively (y-scale).

From a product management perspective, this suggests that for Product 1, with regard to the attribute Fresh, there is a large gap to the level of the best product, i.e., Product 7. So, one could interpret the variation from the status quo to the best level as “room for improvement” for Product 1.

On the other hand, as we can see below, the variables Personality, Original, and Feminine and have a greater Total Effect on Purchase Intent. These relative positions will soon become relevant as we must simultaneously consider the potential for improvement and the importance of optimizing Purchase Intent.

.png)

BayesiaLab’s Export Variations function allows us to save the variation domain for each driver, i.e., the minimum and maximum mean values observed across all products in the study.

Knowing these variations will be useful for generating realistic scenarios for subsequent optimization. However, what do we mean by “realistic”? Ultimately, only a subject matter expert can judge how realistic a scenario is. However, a good heuristic is whether or not a certain level is achieved by any product in the market. One could argue that the existence of a certain satisfaction level for some product means that such a level is not impossible to achieve and is, therefore, “realistic.”

Clicking the Export Variations button saves the Absolute Variations to a text file for subsequent use in optimization.

.png)

.png)

.png)