Chapter 3: BayesiaLab

While the conceptual advantages of Bayesian networks had been known in the world of academia for some time, leveraging these properties for practical research applications was very difficult for non-computer scientists before BayesiaLab’s first release in 2002.

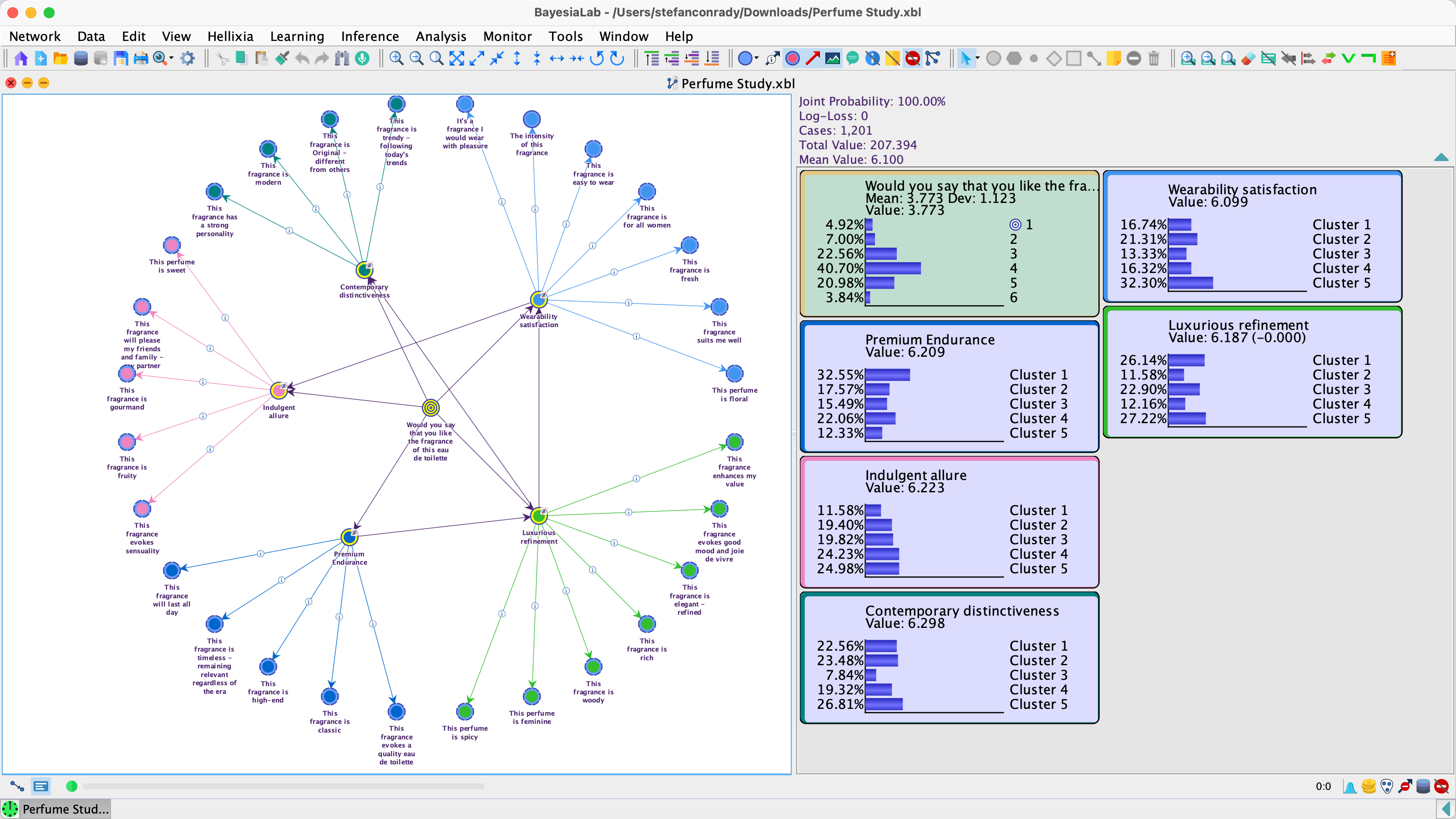

BayesiaLab is a powerful desktop application (Windows/macOS/Unix/Linux) with a sophisticated graphical user interface, which provides scientists with a comprehensive “laboratory” environment for machine learning, knowledge modeling, diagnosis, analysis, simulation, and optimization. With BayesiaLab, Bayesian networks have become practical for gaining deep insights into problem domains. BayesiaLab leverages the inherently graphical structure of Bayesian networks to explore and explain complex problems. The screenshot below shows a typical research project.

BayesiaLab is the result of nearly twenty years of research and software development by Dr. Lionel Jouffe and Dr. Paul Munteanu. In 2001, their research efforts led to the formation of Bayesia S.A.S., headquartered in Laval in northwestern France. Today, the company is the world’s leading supplier of Bayesian network software, serving hundreds of major corporations and research organizations.

BayesiaLab’s Methods, Features, and Functions

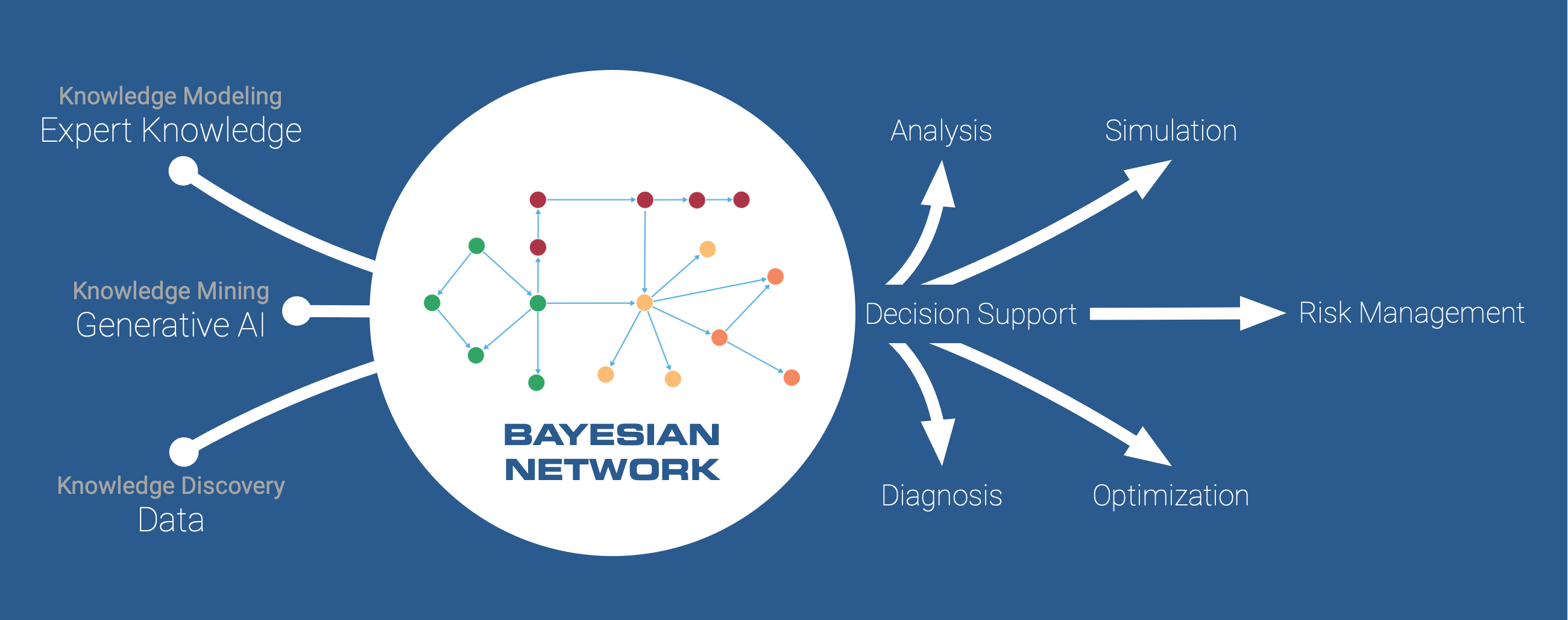

As conceptualized in the diagram below, BayesiaLab is designed around a prototypical workflow with a Bayesian network model at the center. BayesiaLab supports the research process from model generation to analysis, simulation, and optimization. The entire process is fully contained in a uniform “lab” environment, which allows scientists to move back and forth between different elements of the research task.

In Chapter 1, we presented our principal motivation for using Bayesian networks, namely their universal suitability across the entire “map” of analytic modeling: Bayesian networks can be modeled from pure theory, and they can be learned from data alone; Bayesian networks can serve as predictive models, and they can represent causal relationships.

The following “map of analytic modeling and reasoning” shows how our claim of “universal modeling capability” translates into specific functions provided by BayesiaLab, which are placed as blue boxes on this map.

Knowledge Modeling

Subject matter experts often express their causal understanding of a domain through diagrams with arrows indicating causal directions. This visual representation of causes and effects has a direct analog in the network graph in BayesiaLab. Nodes (representing variables) can be added and positioned on BayesiaLab’s Graph Panel with a mouse click, and arcs (representing relationships) can be “drawn” between nodes. As in the following network graph, the causal direction can be encoded by orienting the arcs from cause to effect.

The quantitative nature of relationships between variables, plus many other attributes, can be managed in BayesiaLab’s Node Editor. In this way, BayesiaLab facilitates the straightforward encoding of one’s understanding of a domain. Simultaneously, BayesiaLab enforces internal consistency so that impossible conditions cannot be encoded accidentally. Chapter 4 will present a practical example of causal knowledge modeling, followed by probabilistic reasoning.

In addition to having individuals directly encode their explicit knowledge in BayesiaLab, the Bayesia Expert Knowledge Elicitation Environment (BEKEE) is available for acquiring the probabilities of a network from a group of experts. BEKEE offers a web-based interface for systematically eliciting explicit and tacit knowledge from multiple stakeholders.

Discrete, Nonlinear, and Nonparametric Modeling

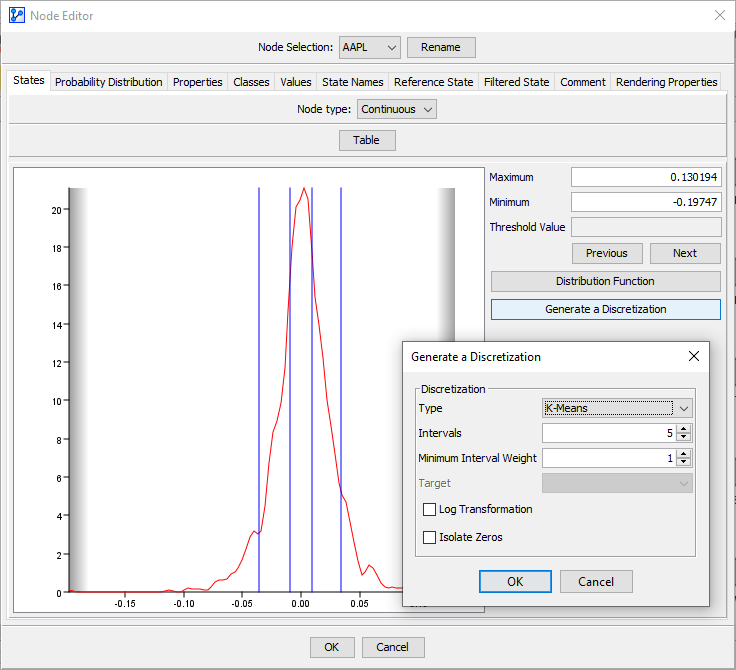

BayesiaLab contains all “parameters” describing probabilistic relationships between variables in conditional probability tables (CPT), which means that no functional forms are utilized. Given this nonparametric, discrete approach, BayesiaLab can conveniently handle nonlinear relationships between variables. However, this CPT-based representation requires a preparation step for dealing with continuous variables, namely discretization. This consists of manually or automatically defining a discrete representation of all continuous values. BayesiaLab offers several tools for discretization, which are accessible in the Data Import Wizard, in the Node Editor (shown below), and in a standalone Discretization function. Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate discretization algorithms are available in this context.

Missing Values Processing

BayesiaLab offers a range of sophisticated methods for missing values processing. During network learning, BayesiaLab performs missing values processing automatically “behind the scenes.” More specifically, the Structural EM algorithm or the Dynamic Imputation algorithms are applied after each network modification during learning, i.e., after every arc addition, suppression, and inversion. Bayesian networks provide a few fundamental advantages for dealing with missing values. In Chapter 9, we will focus exclusively on this topic.

Parameter Estimation

Parameter Estimation with BayesiaLab is at the intersection of theory-driven and data-driven modeling. For a network that was generated either from expert knowledge or through machine learning, BayesiaLab can use the observations contained in an associated dataset to populate the CPT via Maximum Likelihood Estimation.

Bayesian Updating

In general, Bayesian networks are nonparametric models. However, a Bayesian network can also serve as a parametric model if an expert uses equations for defining local CPDs and, additionally, specifies hyperparameters, i.e., nodes that explicitly represent parameters that are used in the equations.

As opposed to BayesiaLab’s usual parameter estimation via Maximum Likelihood, the associated dataset provides pieces of evidence for incrementally updating—via probabilistic inference—the distributions of the hyperparameters.

Machine Learning

Despite our repeated emphasis on the relevance of human expert knowledge, especially for identifying causal relations, much of this book is dedicated to acquiring knowledge from data through machine learning. BayesiaLab features a comprehensive array of highly optimized learning algorithms that can quickly uncover structures in datasets. The optimization criteria in BayesiaLab’s learning algorithms are based on information theory (e.g., the Minimum Description Length). With that, no assumptions regarding the variable distributions are made. These algorithms can be used for all kinds and all sizes of problem domains, sometimes including thousands of variables with millions of potentially relevant relationships.

Unsupervised Structural Learning (Quadrant 2/3)

In statistics, “unsupervised learning” is typically understood to be a classification or clustering task. To make a clear distinction, we emphasize “structural” in “Unsupervised Structural Learning,” which covers a number of important algorithms in BayesiaLab.

Unsupervised Structural Learning means that BayesiaLab can discover probabilistic relationships between many variables without having to specify input or output nodes. One might say that this is a quintessential form of knowledge discovery, as no assumptions are required to perform these algorithms on unknown datasets.

Supervised Learning (Quadrant 2)

Supervised Learning in BayesiaLab has the same objective as many traditional modeling methods, i.e., to develop a model for predicting a target variable. Note that numerous statistical packages also offer “Bayesian Networks” as a predictive modeling technique. However, in most cases, these packages are restricted in their capabilities to one type of network, i.e., the Naive Bayes network. BayesiaLab offers a much greater number of Supervised Learning algorithms to search for the Bayesian network that best predicts the target variable while also considering the complexity of the resulting network (see Chapter 6).

We should highlight the Markov Blanket algorithm for its speed, which is particularly helpful when dealing with many variables. The Markov Blanket algorithm can be an efficient variable selection algorithm in this context. An example of Supervised Learning using this algorithm and the closely related Augmented Markov Blanket algorithm will be presented in Chapter 6.

Clustering (Quadrant 2/3)

Clustering in BayesiaLab covers both Data Clustering and Variable Clustering. The former applies to the grouping of records (or observations) in a dataset; the latter performs a grouping of variables according to the strength of their mutual relationships.

The third variation of this concept is of particular importance in BayesiaLab: Multiple Clustering can be characterized as a nonlinear, nonparametric, and nonorthogonal factor analysis. Multiple Clustering often serves as the basis for developing Probabilistic Structural Equation Models (Quadrant 3/4) with BayesiaLab.

Inference: Diagnosis, Prediction, and Simulation

The inherent ability of Bayesian networks to explicitly model uncertainty makes them suitable for a broad range of real-world applications. In the Bayesian network framework, diagnosis, prediction, and simulation are identical computations. They all consist of observational inference conditional upon evidence.

This distinction, however, only exists from the perspective of the researcher, who would presumably see the symptom of a disease as the effect and the disease itself as the cause. Hence, carrying out inference based on observed symptoms is interpreted as a “diagnosis.”

Observational Inference (Quadrant 1/2)

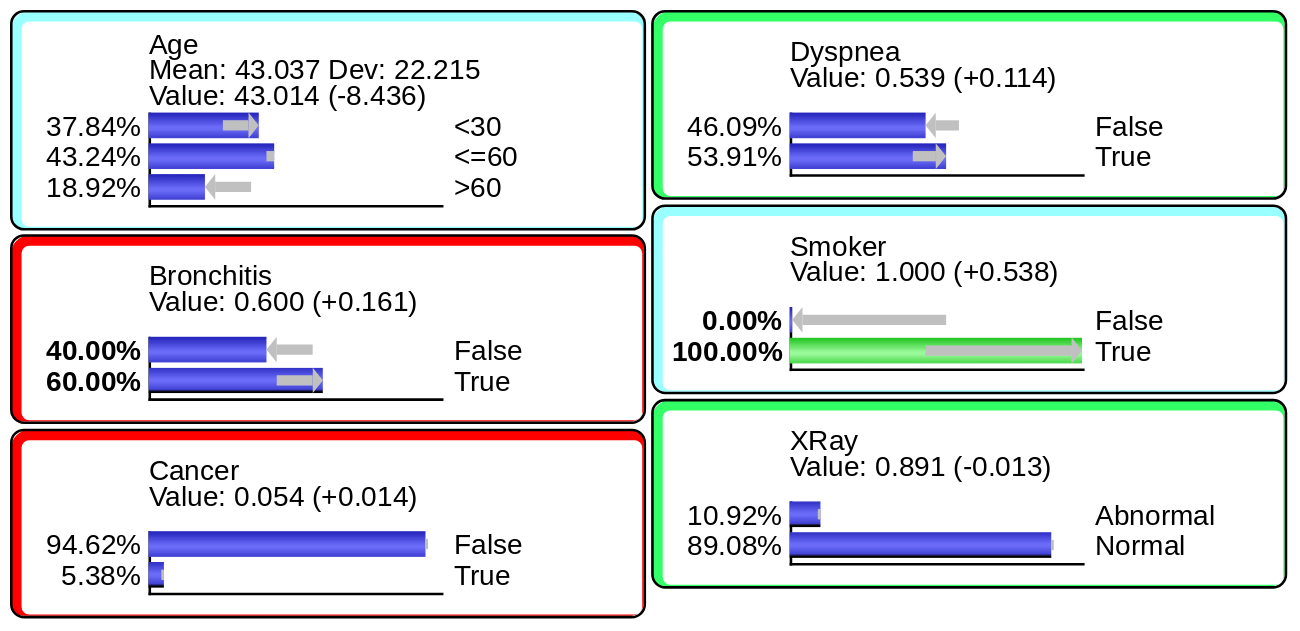

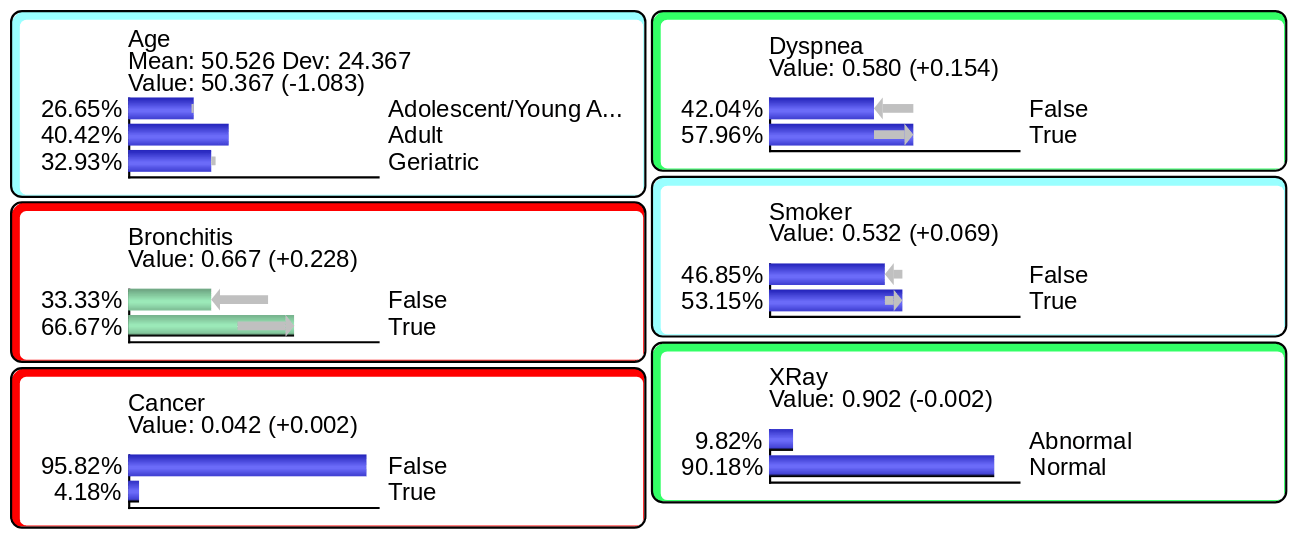

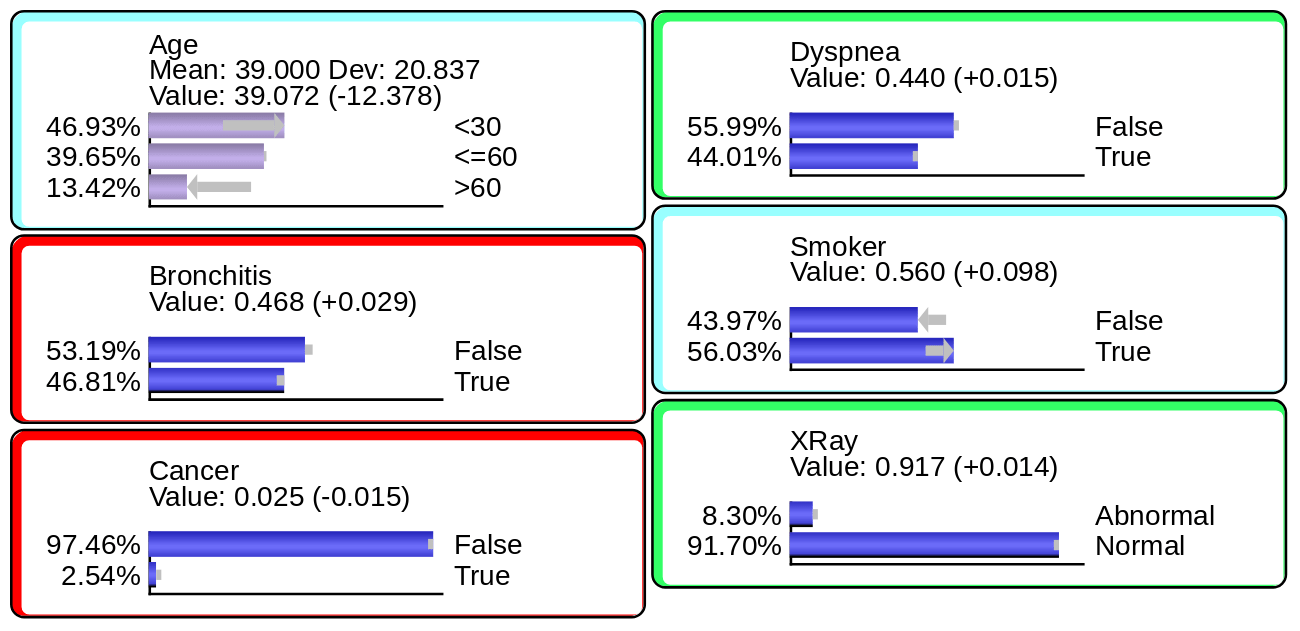

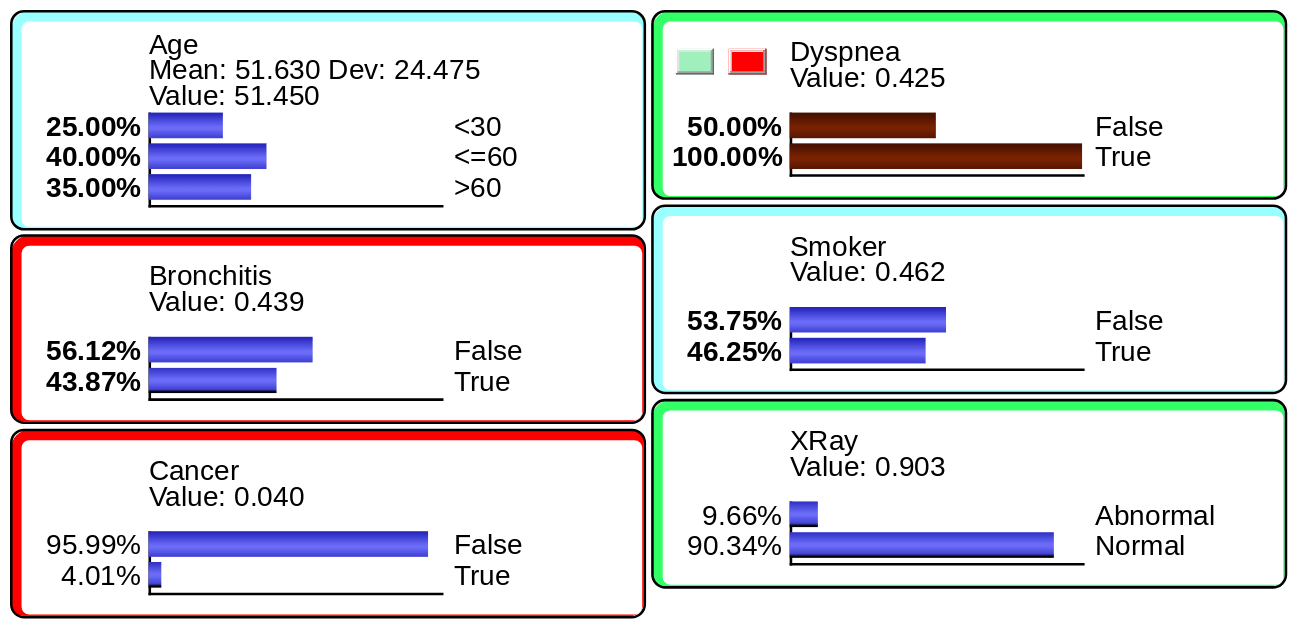

One of the central benefits of Bayesian networks is that they compute inference “omnidirectionally.” Given an observation with any type of evidence on any of the networks’ nodes (or a subset of nodes), BayesiaLab can compute the posterior probabilities of all other nodes in the network, regardless of arc direction. Both exact and approximate observational inference algorithms are implemented in BayesiaLab. We briefly illustrate evidence-setting and inference with the expert system network shown below:

- Inference from effect to cause: diagnosis or abduction.

- Inference from cause to effect: simulation or prediction.

Types of Evidence

Hard Evidence

Hard Evidence has no uncertainty regarding the state of the variable (node), e.g., .

Probabilistic Evidence

Probabilistic Evidence (or Soft Evidence) is defined by marginal probability distributions: .

Numerical Evidence

Numerical Evidence for numerical variables or for categorical/symbolic variables that have associated numerical values. BayesiaLab computes a marginal probability distribution to generate the specified expected value: .

Likelihood Evidence

Likelihood Evidence (or Virtual Evidence) is defined by the likelihood of each state, ranging from (impossible) to (which means that no evidence reduces the probability of the state). The sum of the likelihoods must be greater than to be valid as evidence. Also, note that the upper boundary for the sum of the likelihoods equals the number of states. Setting the same likelihood to all states corresponds to no evidence.

Causal Inference (Quadrant 3/4) chapter-10-causal-effect-identification-and-estimation

Beyond observational inference, BayesiaLab can also perform causal inference to compute the impact of intervening on a subset of variables instead of merely observing these variables. Pearl’s Do-Operator and Jouffe’s Likelihood Matching are available for this purpose. We will provide a detailed discussion of causal inference in Chapter 10.

Effects Analysis (Quadrants 3/4)

Many research activities focus on estimating the size of an effect, e.g., to establish the treatment effect of a new drug or to determine the sales boost from a new advertising campaign. Other studies attempt to decompose observed effects into their causes, i.e., they perform attribution.

BayesiaLab performs simulations to compute effects, as parameters as such do not exist in this nonparametric framework. As all the domain dynamics are encoded in discrete CPTs, effect sizes only manifest themselves when different conditions are simulated. Total Effects Analysis, Target Mean Analysis, and several other functions offer ways to study effects, including nonlinear and variable interactions.

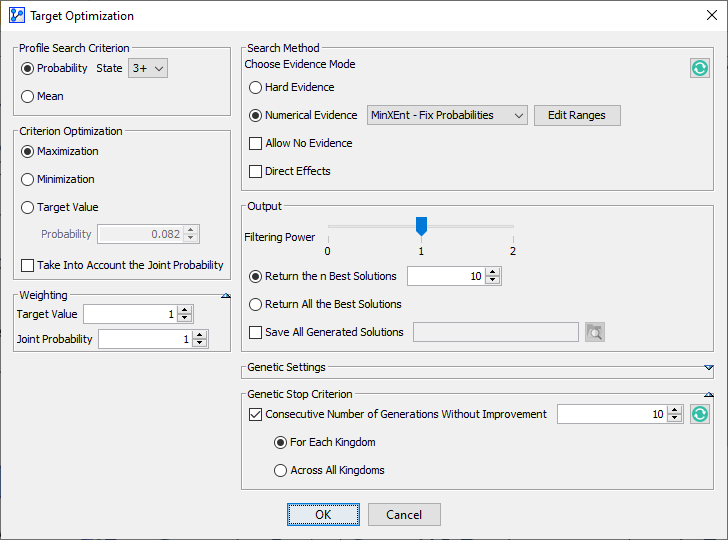

Optimization (Quadrant 4)

BayesiaLab’s ability to perform inference over all possible states of all nodes in a network also provides the basis for searching for node values that optimize a target criterion. BayesiaLab’s Target Dynamic Profile and Target Optimization are a set of tools for this purpose.chapter-8-probabilistic-structural-equation-models-for-key-driver-analysis

Using these functions in combination with Direct Effects is particularly interesting when searching for the optimum combination of variables with a nonlinear relationship with the target, plus co-relations between them. A typical example would be searching for the optimum mix of marketing expenditures to maximize sales. BayesiaLab’s Target Optimization will search, within the specified constraints, for those scenarios that optimize the target criterion. An example of Target Dynamic Profile will be presented in Chapter 8.

Model Utilization

BayesiaLab provides a range of functions for systematically utilizing the knowledge contained in a Bayesian network. They make a network accessible as an expert system that can be queried interactively by an end-user or through an automated process.

The Adaptive Questionnaire guides in terms of the optimum sequence for seeking evidence. BayesiaLab determines dynamically, given the evidence already gathered, the next best piece of evidence to obtain in order to maximize the information gain with respect to the target variable while minimizing the cost of acquiring such evidence. In a medical context, for instance, this would allow for the optimal “escalation” of diagnostic procedures from “low-cost/small-gain” evidence (e.g., measuring the patient’s blood pressure) to “high-cost/large-gain” evidence (e.g., performing an MRI scan). The Adaptive Questionnaire will be presented in the context of an example of tumor classification in Chapter 6.

The WebSimulator is a platform for publishing interactive models and Adaptive Questionnaires via the web, which means that any Bayesian network model built with BayesiaLab can be shared privately with clients or publicly with a broader audience. Once a model is published via the WebSimulator, end users can try out scenarios and examine the dynamics of that model.

Batch Inference is available to automatically perform inference on a large number of records in a dataset. For example, Batch Inference can be used to produce a predictive score for all customers in a database. With the same objective, BayesiaLab’s optional Export function can translate predictive network models into static code that can run in external programs. Modules are available that can generate code for R, SAS, PHP, VBA, and JavaScript.

Developers can also access many of BayesiaLab’s functions—outside the graphical user interface—using the Bayesia Engine API. The Bayesia Modeling Engine allows the construction and editing of networks. The Bayesia Inference Engine can access network models programmatically to perform automated inference, e.g., as part of a real-time application with streaming data. The Bayesia Engine API was recently augmented with a model learning capability, which allows programmatic access to BayesiaLab’s learning algorithms. This functionality is ideally suited for machine-learning models from streaming data.

The Bayesia Engine API is implemented as pure Java class libraries (jar files), which can be integrated into any software project.

Knowledge Communication

While generating a Bayesian network, either by expert knowledge modeling or through machine learning, is all about a computer acquiring knowledge, a Bayesian network can also be a remarkably powerful tool for humans to extract or “harvest” knowledge. Given that a Bayesian network can serve as a high-dimensional representation of a real-world domain, BayesiaLab allows us to interactively—even playfully—engage with this domain to learn about it. Through visualization, simulation, and analysis functions, plus the graphical nature of the network model itself, BayesiaLab becomes an instructional device that can effectively retrieve and communicate the knowledge contained within the Bayesian network. As such, BayesiaLab becomes a bridge between artificial intelligence and human intelligence.